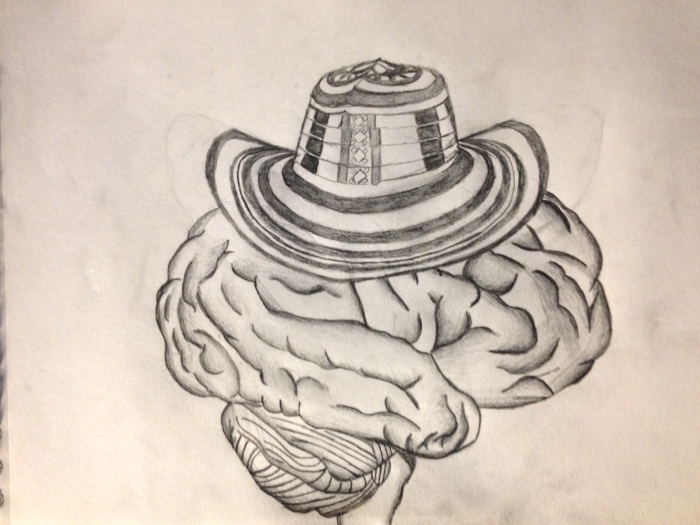

Culture Affects Brain Structure and Function

When immersed in a new culture we often become cynical after the “honeymoon stage.” We get anxious or depressed, and we complain, throwing blame at anyone and everything related to the unfamiliar culture. We may ask accusatory questions, “Why don’t people use their blinkers here? Why don’t people stop at stop signs? Why do people talk so loud? Why do the lines in the grocery store take so long?” “It’s all because of the culture!” we say.

We can bypass the cynicism by joking about the cultural practices and developing behaviors to live harmoniously, if only on the surface. But perhaps, in this way, we never fully acculturate. Even if we try to tolerate the culture and develop personal coping mechanisms to accept differences, we may still be only pretending to acculturate, leaving ourselves vulnerable to a biological sneak-attack. Adapting to a new setting takes time. I like to think of myself as a tolerant, understanding person that easily adapts to new regions and cultures, but I have realized, through research and my four years in Barranquilla, that I need to be patient with my brain.

We try to modify our behaviors when our brains aren’t ready, or we often immerse ourselves too deeply, too soon. The problem is two-fold: first, we can’t see a scan of our own brain on a daily basis, and, therefore, we cannot fathom the havoc that stress is wreaking on our amygdalae. Second, a low-point can arrive suddenly, hitting us like a brick wall. In light of these two factors, learning about the neuroscience behind cross-cultural living is just as important as the behavioral sciences. If we recognize cerebral conflict, we may not fall into the infernal depths of pessimism.

Many studies have shown that the structure and function of our brains can be shaped by the context in which we live. Since the sensory stimulation we receive plays a major role in how our brains develop physically, the culture that surrounds us can have drastic biological effects. In Rick Hanson’s Buddha’s Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love, and Wisdom, he consistently repeats the phrase, “Neurons that fire together wire together.” If that is the case, the culture in which we grow up wires our neurons according to the stimulation it receives from the surrounding culture. Our brains get comfortable with our surroundings, and we begin to expect the things that have always been consistent in our lives. Furthermore, our brains lose neuroplasticity as we get older, and because we are less able to rewire our brains, we experience mental conflict when we are thrusted into unfamiliar situations.

After firing my neurons for so long in Minnesota, I have wired certain cultural practices into my brain. Every little cultural nuance, in a way, has become an expectation. Without consciously thinking it, our brain begins to believe that “this is the way it should be” when we continually come across a cultural practice. My stubborn subconscious has also traveled with me to barranquilla where I have realized that others in the world think differently about, “the way it should be.”

Thwarted expectations lead to stress, and stress leads to increased anxiety and poor brain performance. Living in a new culture, we are never sure of what to expect. Even going to the grocery store, where we are not sure if we will be able to understand the cashier when she tells us that the coffee is half-off, is a risky venture. The longer our brains are in conflict with our surroundings, the harder it is to cope with cultural differences and thwarted expectations.

My Vulnerable Brain

The vulnerability of my brain first became apparent when I was riding the bus home after a stressful day at school. My brain was already fried as I had spent the day trying to figure out how to better manage my classroom and adapt my teaching style to a new culture. On this particular day, the bus driver was ahead of schedule and decided to drive at a snail’s pace, despite transporting a busload of passengers. I had nowhere to go in a hurry, but I wanted to get home, isolate myself from the world and maybe read a book (in English!) silently in my bedroom.

My blood pressure was rising as the driver continued at a snail’s pace. I started to look around me, saying to other passengers, “tengo prisa” “I am in a hurry.” I wanted someone on the bus to empathize with me, perhaps join my cause as I tried to form a mutiny. To my dismay, I got blank stares. No one else was in a hurry. I started to curse under my breath, and then I shyly spoke up. “Vamos,” I said, more out of frustration than to actually be heard. The bus driver didn’t hear me, and what he did next put me over the edge. The light at which we were stopped turned green, and he didn’t move. I looked up from the self-pity in which I was wallowing and realized that, instead of stepping on the gas, the bus driver was ordering an arepa from a street vendor, but his arepa wasn’t even ready yet!

By the time he got his arepa, the light had turned red again. I shot up out of my seat, shouting, “this is ridiculous!” Everyone was staring at me, and I am afraid not a single one of the passengers knew why I was so frustrated. Some might have even been afraid of how angrily I shot out of my seat, but my rage clouded my memory of anyone’s facial expression. I bolted to the back door and quickly pushed the button to be let off. My anger prevented me from foreseeing the six miles I would have to walk from there to my apartment.

In hindsight, I am aware that I overreacted. I let my brain get to a breaking point, and as a consequence, I turned into the crazy Gringo on the K54 bus. I had no more room for thwarted expectations that day, and since my brain had been wired differently, I didn’t expect the driver to go at a snail’s pace and grab an arepa on the way home. My brain had been previously wired to be in more of a hurry and to anticipate more professionalism from the bus drivers. Like the others on the bus, I could have been indifferent to the laid-back, no-hurry attitude, and, in fact, I have come to appreciate that part of the culture more and more. I blew up because my xenophobic neurons couldn’t take that one last jab, so they ferociously swung a knockout punch at its new invaders.

Our Fear of the Unknown

Research continues to surface arguing that different cultures cause different “patterns of neural activation.” In one such study, Azar (2010) found that the brain activity of a Chinese man versus that of an American man is entirely different when considering traits of themselves and others. Azar argues that a greater focus on collectivism in Chinese culture as opposed to individualism in American culture causes their neurons to fire differently. Similarly, if I am wired to think differently than a Barranquillero in similar situations, there is bound to be conflict eventually, especially if I forget to take a break from the culture and burn myself out.

As foreigners we are constantly bombarded with unfamiliarity, and, naturally, as humans we fear unfamiliarity because there is always risk involved. Not knowing if we will get lost or wondering if the store clerk understands us can produce fear. Outside of our apartments, we are in a constant state of fear (although maybe subconscious) that is causing stress. It may not be the fear we get from the wildlings in the television series Game of Thrones, or the sensation of jumping out of an airplane, but it is a constant feeling of uncertainty. This fear is processed in the amygdala. It creates an emotional response and initiates stress reactions in the brain, thus making it more difficult to process environmental events in the future. It’s a vicious cycle that, when ignored, will lead to a downward spiral and maybe even an embarrassing out-lash at a bus driver.

When left untended our conflicted brains can suffer serious consequences, maybe resisting the new culture’s rewiring of our brains, or worse, refusing to learn anything knew. For instance, in language learning, researchers have identified what is called an “affective filter.” This filter is referring to all the emotional responses, like anxiety, fear and depression, that prevent us from learning according to our full potential. In theory, anxious people are much less likely to retain knowledge. Therefore, complete immersion can have the opposite effects that we want, causing us to withdraw from the culture instead of embracing it. I find that some of the best ways of sidestepping the affective filter is to take mind vacations from the culture. I might log-in to Netflix to watch a few shows from the United States or spend a weekend reading the novels I brought from the US.

In a harmful emotional state we may not only experience learning deficiencies, but we can also experience a harmful synaptic rewiring. If through the media and word of mouth we are fed images of negative associations related to a particular culture or people, we will subconsciously begin to take those associations as truth. One of the best ways to see what kinds of biases have been ingrained in our brains is by taking Harvard’s Implicit Association Test. Most people are surprised to see that they actually have negative biases toward certain races and cultures. It’s not because we are racist or bad people, but because our brains have been wired by our surroundings. We subconsciously begin to believe what we are exposed to.

Making the Unfamiliar Familiar

Our music tastes can easily illustrate our brain’s process of acculturation. Daniel J. Levitin, in his 2006 book, This is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession, argues that the music most appealing to us is largely familiar but also has an element of surprise. Over time, our culture conditions us to enjoy our own music as long as it doesn’t become too monotonous. When I first arrived in Colombia, the genres of music didn’t come across as much more than a bunch of noise. I found that I usually craved my own music. I went out to salsa clubs with an open mind, learned how to dance salsa, merengue and champeta, but I didn’t really experience any positive emotions from the music itself until after I had been here for a couple of years. In time I began to recognize the combinations of certain instruments, latin beats, and novel rhythms. Now I even have favorite songs that I learned in Barranquilla and will listen to back in the United States. The champeta of Kevin Flores and the salsa of Joe Arroyo is now some of my favorite music.

Over time I think I have developed a bicultural brain, but it required me to walk a tight rope between familiarity and overstimulation. Acculturation requires an awareness of our mental states. By paying attention to how we are feeling, and giving ourselves necessary “Gringo vacations,” we can more successfully immerse ourselves into the culture and rewire our brains when we are ready for it. Despite our decreasing neuroplasticity, anyone can have a bicultural brain, and, if you ask me, it’s worth it.

Sources:

Azar, Beth. “Your Brain on Culture.” American Psychological Association. November 2014, Vol. 41, No. 10.

Ledoux, Joseph E. “The Amygdala: contributions to fear and stress.” Seminars in Neuroscience. August 1994, Vol. 6, Issue 4.

Lende, Daniel. “Cultural Neuroscience: Culture and the Brain.” Weblog post. PLOS Blogs. N.p., 26 Nov. 2010. Web. 26 Apr. 2014.

Nalini, Ambady. “The Mind in the World: Culture and the Brain.” Association for Psychological Science RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Apr. 2014.

Wexler, Bruce E. Brain and Culture: Neurobiology, Ideology, and Social Change. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2006. Print.

Let’s talk more about staph infections.

I think you need to write a guest post on the topic, Greg.